The inventor of tactile literacy, Louis Braille, was born in Coupvray, France, on January 4, 1809. Louis was born sighted, but he became blind when, at the age of three, he accidentally poked himself in the eye with a sharp tool from his father’s leather workshop. An infection resulted in both eyes, rendering him totally blind by the age of five.

Louis went to school at the Royal Institute for Blind Youth in Paris. At that time, the only method blind people could use to access the written word, besides listening, was to read books containing raised print letters made out of wood or wire. Such books were bulky and the reading process was inefficient. Louis longed for a tactile reading system that would give him the same efficient access to books as his sighted peers enjoyed in print.

When Louis was twelve, a man named Charles Barbier visited the school. Barbier was working to develop a tactile code that French soldiers could use to exchange secret messages in the dark. Louis was intrigued by Barbier’s code, known as “night writing.” Over the next three years, Louis simplified and standardized the code, and the first braille alphabet was born.

Simply put, all braille symbols consist of dots arranged in a “cell”, or a grid 2 dots wide and 3 dots high. Each symbol is represented by a different combination of dots. There are 64 possible braille symbols in total, including a space (made by creating an empty cell with no dots present). Louis Braille’s code focused on the 25 symbols corresponding to letters of the Roman alphabet (excluding W, which was absent from the French alphabet at the time). The first ten letters are made by combining dots in the upper two-thirds of the cell; for letters K-T, the lower left dot is added to letters A-J; and for letters U, V, X, Y, and Z, the lower right dot is added to K, L, M, N, and O respectively. Some of the remaining dot combinations are used as punctuation marks or mathematical symbols in Louis Braille’s original code. At a later point, the English braille code was modified to turn additional dot combinations into “contractions” that make braille easier and faster to read; for example, the word “for” is written as a single symbol consisting of all six dots. Numbers can be written either by placing a symbol called a “number sign” just before letters A-J (to represent numbers 1-9 and 0, respectively) or by writing letters A-J one dot lower in the cell to represent numbers 1-9 and 0, respectively. A separate code for braille music was also created.

Louis Braille published his first brailled book in 1829. The oldest, most basic braille writing device was a stylus, ironically similar to the tool that caused Louis’s blindness, that can be used to punch the braille dots through a piece of paper. Many braille users today still use a stylus along with a slate, which holds the paper in suspension so that dots can be punched through with appropriate spacing. Modern braille writing implements, as I will discuss next week, can make braille production smooth and efficient.

Although students at the Royal Institute for Blind Youth liked Louis Braille’s code, it was not taught there officially until after his death in 1852. Teachers and principals at schools for the blind in other parts of the world showed a remarkable resistance to adopting braille. In the United States, various other tactile codes were introduced as alternatives to braille. Most of these codes, such as Boston line type and New York point, were written to resemble conventional print. Sighted educators preferred for their students to use codes that they could read and write themselves. Analogous to “oralist” movements emphasizing speech and lip-reading for deaf students, it was thought that blind students should use print-based literacy in order to avoid isolation from the broader sighted community. However, these print-based alternatives were difficult to read efficiently. They were unstandardized, so students educated in one code may have had limited access to books written in that code. Some students at schools for the blind began secretly using braille to communicate with one another. Eventually, the simplicity and efficiency of braille was recognized, and braille was adopted as the international standard of tactile literacy. Louis’s birthday, January 4, is commemorated as “World Braille Day.”

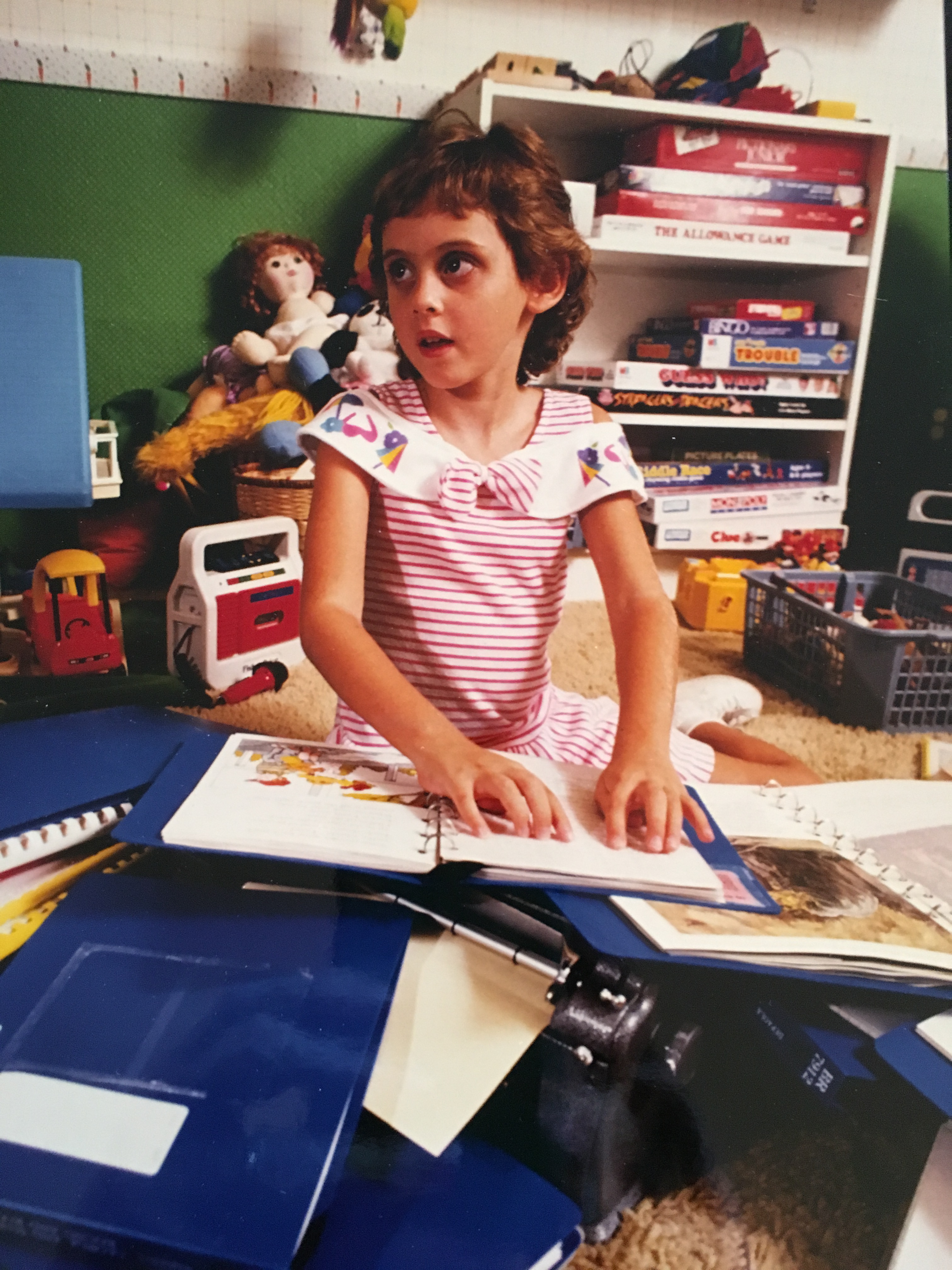

Louis Braille’s biography was one of the first braille books I ever read, while I was still mastering the contractions and building my reading comprehension skills. The picture shows me reading braille (though probably not that particular book) at the age of six.

Louis Braille’s life and work made a real impression on me. He was an example of a disabled person who refused to follow the path that society prescribed for disabled people of his time. Instead, he found a solution that made life better not just for him, but for the entire blind community present and future. He used his own disability experience to develop a simple yet elegant solution that has proven itself superior to other methods. The backlash that Louis received is just one example of a trend of nondisabled authorities guarding their power by explicitly or implicitly rejecting disabled people’s leadership in empowering themselves. Today, even though most blind children are no longer educated at segregated schools for the blind, conflicts surrounding the use of braille still rage. I will write more about modern braille debates next week.